A History of Wallets and Purses.

Share

Origins of the Wallet: A Mythical Story.

Go on, take out your wallet. That leather pouch that lives in your pocket.

Feel its familiar weight, the worn leather, the heft of it in your hand. You think it just holds your money and cards? It holds a secret history, a story too.

The Origins of the wallet begins in the realm of myth. The ancestor of the wallet, the Greek kibisis, was a sack of mythological proportions, the chosen accessory of the god Hermes and famously used by Perseus to carry the head of Medusa.

Amphora depicting Perseus rescuing Andromeda from Ketos, in the Altes Museum, Berlin | Link to artwork

This divine connection isn't unique.

Kubera - Circa 1st Century CE - Kosi Kalan Government Museum - Mathura | Image Link

In Indian mythology, Kubera, the treasurer of the gods, is rarely seen without his overflowing money bag, a symbol of his dominion over all wealth. Across Asia, Caishen, the Chinese God of Wealth, holds a similar pouch, bestowing prosperity.

This is an AI Generated Image

From the very beginning, the act of carrying our provisions, our wealth, our very potential, has been seen as something sacred. The journey from that divine story to the wallet you own is a fascinating tale of money, merchants, and the things we choose to hold close.

Wallets from the Middle Ages: A Series of Changes

Wallets from the 13th Century: A wallet wasn’t always a wallet.

In the early 13th century before the term Wallets came into use, people used pouches to carry around coins and religious symbols such as paternoster later known as prayer beads or rosaries along with a small wax tablet and a stylus. It was usually worn around the belts and were sold together. As mentioned in this blogpost about medieval fashion: these types of purses were called aumônière or alms purses in English. They seem to have gotten their names from the Christian religious duty of providing alms and eventually the term seems to have caught on as an over-all term for pouches that people carried with them.

A mid-14th century French purse on display at the Met Cloisters in New York

The word “Wallet” first appeared in English in the late 1300 as ‘walet’, which meant a bag, more akin to a backpack or a satchel than the slim wallets of today. The origin of the word is uncertain, but etymologists point towards the Proto-Germanic root, “wællan” which basically means a container for valuables that could be rolled or bundled up. For centuries, this is what a wallet was: a simple bag for a traveler's or a pilgrim's food and personal items. The term wallet took on many different meanings and forms carrying everyday precious and necessary items, before currency became common and the most essential part. Before it shrank into a container for money and valuables.

The wallet and purses began to mirror our changing social norms. Dr. Russell Belk, a leading expert in consumer culture and materialism, argues that our possessions are a significant part of our identity, calling them the "extended self." In his influential 1988 paper, Possessions and the Extended Self - Journal of Consumer Research he writes, “we are what we have.” The wallet, became a primary example of this—a small object that says a great deal about our personal taste, things we value, and status.

Evolution of the Wallet from the 15th to 18th Century: Girdle, Purse and Batua.

In medieval Europe, the predecessor to wallets were girdles— pouches made from cords of fabric worn at the waist. For the nobility, these were not mere accessories. Knightly girdles were made of ornamented, linked-metal sections, a clear signifier of rank. Claire Wilcox, in her book. Bags, published by Victoria and Albert Museum, mentions that women’s girdles became deeply ornate, crafted from patterned silk. Their symbolic power was so great that the 15th-century writer Oliver de la Marche, in his treatise “The Adornment and Triumphs of Ladies,” described the girdle as an accessory that represented a woman’s very virtue.

Portrait of :Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester. Carrying a Girdle Pouch attached to his belt. Image Source

In the first half of the seventeenth century, purses shaped from two pieces of fabric which closed with double drawstrings and embellished with tassels appeared around the sleeves and belts. Worn by both men and women, the most luxurious ones were made with embroidered silk, bead work on leather and rich velvet. Used as a gaming bag with draw-string closure to keep the winnings of gambling money. Not exclusive to just money and personal trinkets, they were also used as decorative containers for gifts such as perfume or jewels. A list of the contents for such a pocket with a purse can be found through an advertisement requesting the finder of a lost purse to return it to the owner published in a weekly journal in 1725.

“D[r]opp'd between St. Sepulchres church and Salisbury court in fleet-street, going down fleet-lane, and crossing the bridge, a pair of white fustian pockets, in which was a silver purse, work'd with scarlet and green S.S. In the purse there was 5 or 6 shillings in money; a ring with a death at length in black enamell'd, wrapp'd in a piece of paper; a silver tooth pick case; 2 cambrick handkerchiefs, one mark'd E.M. the other E5D; a small knife; a key and pair of gloves, and a steel thimble. If the person who took them up will bring them to Mr. Peachy's at the black boy in the o'd baily, he shall receive a guinea reward, ann no questions ask'd.”

Mist's Weekly Journal (London), 22 May 1725 | Reff: Victoria and Albert Museum

An AI Generated Image Inspired by the original design at Victoria and Albert Museum.

An AI Generated Image Inspired by the original design at Victoria and Albert Museum.

This wasn't just a European phenomenon. In the opulent courts of princely India, ornate purses (batuas) made from rich, embroidered silk and embedded with jewels served the same purpose. The word Batua means a small bag of leather or cloth with partitions on its inner side. A famous variation of this design is known as a Bhopali Batua. This type of a purse is adorned with zardozi (embroidery with metal threads) and bead work and was used for keeping paan (beetle leaves), laung(cloves), itar(perfume) and other fragrant materials by the royals and subsequently, coins and currency. As part of souvenir and gifts the Bhopali Batua came to be a part of a local couplet that firmly cemented its relevance to the culture and the city.

“Char cheez taufie Bhopal, Batwa, Ghutka, Chuneti aur Roomaal”

(Four things are worth taking as presents from Bhopal, a batua (small purse), gutka( fragrant mixture of cloves, areaca nut, rose petals, cadamoms), chuneti(a tiny box used for keeping lime) and a roomal (handkerchief).

Made in 1862, Varanasi, India. Description: A Black velvet purse, lined with white silk, and embroidered with flattened silver wire and sequins, and a silver fringe. | Source Image: Victoria and Albert Museum

Based on the findings by Dr Meeta Siddhu, in her research she mentions, as a means to carry pan, Batua came to be patronised and popularised by the royal families of Bhopal. They were made with opulent fabrics such as tanchoi kumkhwab (silk brocade) velvet, silk and satins and embroidered with precious stones, sequins, metallic discs, beads, with metallic threads. Their Design was essentially semi-circular in shape with four compartments called char-khana Batuas, meant to carry ingredients of the beetle leave, ie. Pan. Eventually when Batuas transformed to carry currency and coins, they were larger in size and were called teen-khana or three partitions. With a heavy Persian influence, these batuas came with ornate tassels being used to fasten them to the belt. Eventually it became a symbol of status and the pride of Bhopal. Today Batua’s are used as fashion accessories in weddings, functions and get-togethers often worn with traditional clothes.

This is an AI Generated Image based on the description of an modern Bhopali Batua design.

This is an AI Generated Image based on the description of an modern Bhopali Batua design.

Purses, Girdles or Batuas, across cultures, the message was the same: what you carried your wealth in was as important as the wealth itself.

The Paper Revolution & The Industrial Age

The Origin of the wallets as we know them today, started with pockets. Pockets were initially not a part of the clothing but a separate article that continued to be tied around the waist for men and for women, they were hidden among the folds of the petticoat and reached through slits. These pockets lent its name to other portable accessories such as the pocket book or pocket case and the pocket handkerchief. As noted by the Royal School of Needlework, embroidered pocket books gained popularity in the 18th and early 19th century and were used to keep essentials like money, letters and shopping lists.

1780-1800 teal green satin pocket book with two flapped pockets on the inside and overall quilting. A possible gift of Queen Mary - Royal School of Needlework

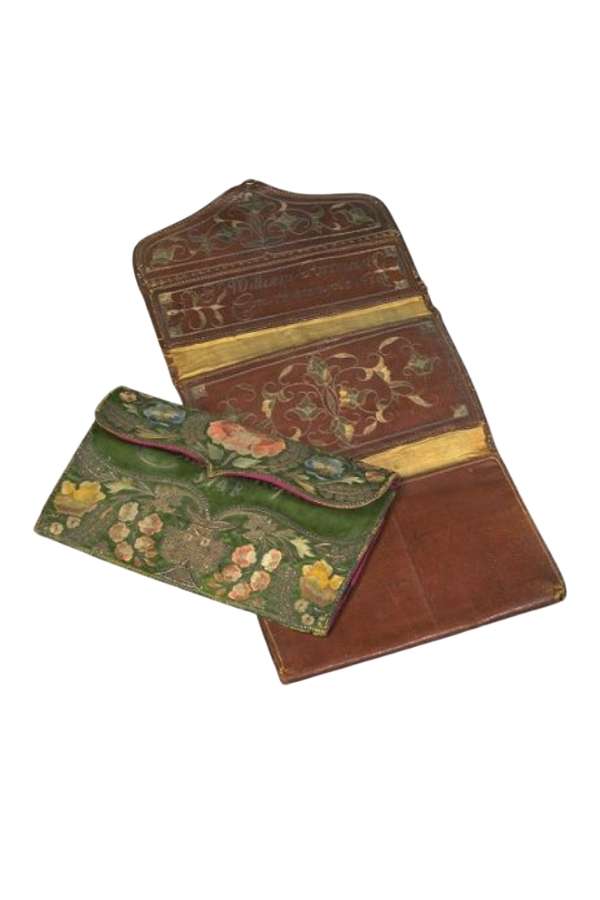

Larger pocket cases with divided pockets were used to hold letters, calling cards, bank bills and documents of value. These pocket cases took a dramatic turn in the 17th century with the advent of paper money. With increasing popularity of transactions through paper bills, it demanded a modification of the pocket cases. Leaving behind the round, soft coin purse as it was useless for large bills and leading to the birth of the flat folder design—called the “billfold.”

Leather wallet lined with silk and embroidered with metal threads, Istanbul, dated 1682. Textile Research Center

The Industrial Revolution then supercharged this evolution. As people traveled, traded, and interacted in new ways, their needs diversified, leading to an explosion of wallet designs: the organized Accordion Wallet, the globetrotting Travel Wallet, and the charming Kiss-Lock Coin Pouch. The wallet was no longer one-size-fits-all; it was a specialized tool for a rapidly changing world.

From A President's Pocket, to A Soldier's Hope

On the night of April 14th 1865, in the balcony of the Ford Theater, a man called John Wilkis Booth crawled up with a pistol in his hand and shot at point blank range, one of the most important figures of the 18th century, Abraham Lincon. At the time of the shooting, among other things in his pocket, Mr Lincon had a brown leather trifold wallet that was lined with purple silk, its compartments embossed with gold lettering: “Notes,” “U. S. Currency,” and “R. R. Tickets.” These pockets suggest what a person from the middle of the 19th century might need to carry with him: paper notes, paper money, and paper railroad tickets.

Wallet carried by Abraham Lincoln on the night of his assassination, April 14, 1865. Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress.

Perhaps no wallet represents or tells a better story of its form, function and value in the 18th century more than the one found in Abraham Lincoln's coat pocket on the night of his assassination. Now housed in the U.S. Library of Congress, it contained a five-dollar Confederate bill (likely a souvenir of victory in the civil war) and eight newspaper clippings of the time. As the Library’s curators note, while the wallet is associated with his death, "the contents speak more to how he lived."

This transformation of the wallet into a personal archive wasn't just for presidents. Scattered in museums like the Imperial War Museum in the UK, and multiple war memorials and museums across Korea, India and Japan are wallets from soldiers, survivors and refugees in the World Wars and the shifting political lines of the preceding years. These humble leather objects didn't just carry money; they carried letters from home, photos of loved ones and tiny tokens of memory—a tangible connection to a life they prayed to return to and a memory of what they had left behind. The wallet didn't just hold currency, it had become a sanctuary.

Albert Tattersall died (aged 23) on 3 July 1916 of wounds received on 1 July 1916, serving with 'A' Company of the 20th Battalion, The Manchester Regiment (5th City Pals). In addition to his letters (with Documents Department) and his service medals, the IWM holds his personal effects which were sent home after his death (at a Casualty Clearing Station): pipe, tobacco pouch, pocket knife, scissors, tin of cigarettes, tin mirror, and identity disc. : Imperial War Museum

Wallets of the 20th Century: The Modern Wallet.

Voluptuous and Prosperous to the Slim and Efficient.

Fast forward to the 1950s. People started shedding the heavier clothes of the yester years, and dawned lighter and more flexible clothing that suited a faster and more modern way of life. In this changing world, the credit card arrived, and became a popular, modern way of making payments, fundamentally changing the wallet's design. After the wars, and the beginning of the economic boom, wallets suddenly got busier. They needed slots, then more slots, and then by the 80’s and 90’s they needed windows for IDs and coin pouches, a slot for a key and secret pockets and ohh yes they also needed to be smaller and lighter.

This is an AI generate Image of a typical wallet design from the 1950's.

As a symbolic association with storage of money and valuables, the myth of the fat wallet rose in popular culture. A bulging wallet full of cash or card that was interpreted as a sign of wealth, success, or financial security took root in people’s imaginations. And this brought about the dawn of the "Costanza wallet" (referred from a famous episode of the TV Show, Seinfeld)—that overstuffed, chiropractic nightmare our fathers and uncles shoved down their trouser pockets, a Pandora's box of visiting cards, faded receipts, and odd bills, threatening to explode at the seams.

And then, as we were slowly moving towards a slimmer, more compact version of the wallets, in the second decade of the 20th century, for us in India, came the great unstuffing. The Demonetisation of 2016 was a seismic shock. Overnight, our relationship with cash was thrown into chaos. Democratised digital transactions along with the pandemic and the roll out of the United Payment Gateway, made cashless transactions the norm almost overnight, and it forced us to ask, especially among the younger generation, what is this wallet really for?

Front Page from The Indian Express Dated 9th November 2016, a day after Demonetization was declared by the Indian Government.

Front Page from The Indian Express Dated 9th November 2016, a day after Demonetization was declared by the Indian Government.

The answer, we discovered, was hidden in its folds.

Wallet, a case for hopes, memories and dreams.

To truly understand the modern wallet, we must see it as a pocket-sized museum of the self. As the authors of "Materiality" from Duke University Press aptly state, "Humans are defined, to an extraordinary degree, by their expressions of immaterial ideals through material forms."

Beyond borders and cultures, in our cities or in foreign lands, the wallet is a personal museum and a portable shrine. Holding a tiny photo of a deity, a sacred thread from a puja, that lucky ₹50 note or a blessed talisman. It’s a container of hopes. Along with a few currency bills for emergencies, our wallets carry memories of our relationships: worn photos, a movie ticket stub from a first date, a handwritten note, maybe a dried flower petal. These small hidden objects that are as precious as any treasure.

Which is why losing a wallet feels like a personal violation. It's not just the Aadhar Card or the Debit and Credit Cards; it's the loss of this irreplaceable collection that grounds us, makes us feel connected and secure. These items not only hold a personal association, but reach out to strangers as well. In a famous study, psychologist Professor Richard Wiseman found that wallets with a baby photo were far more likely to be returned—these personal tokens trigger a deep-seated compassion, reminding us and telling others that the contents are personal and priceless.

This deep emotional significance and the close association of walleths with their owners and their daily lives, makes the wallet a perfect vessel for memory across generations and cultures. Just like a watch or a piece of jewellery, an inherited wallet carries the imprint of the previous owner's life. When made from durable, gracefully aging materials like leather, wallets retain their functionality over time and become precious heirlooms. Often given as gifts to mark a first job or a new beginning, they are a symbol of prosperity and hope. As new gifts or inherited heirlooms, combining personal history, material durability, social and symbolic meaning, wallets have become carriers of memory and identity across generations and cultures.

Digital Wallets V/s Physical Wallets.

When wallets become a digital ghost.

Just as the wallet reached its peak as a personal archive, the digital wallet arrived. There is no doubt about the functional advantages, the regulatory benefits, the usability and the ease of QR Codes, Payment through Apps and phone numbers or even, just a tap of the card. But did we lose something in this frictionless and effortless future of payment?

Photo by Ivan Samkov from Pexels

Behavioral science highlights the "pain of paying," the psychological friction we feel when parting with physical cash. A digital tap is less mindful. It's not about crying foul towards technological advancements, we should be grateful for the ease and inclusion of these in our daily lives, and as thinking individuals we should also realise that we have lost a simple yet an effective ritual that helped us save those pennies. We have lost the serendipity of rediscovering an old photo or a totem while shuffling through for cash, we have lost those brief conversations we sometimes had with vendors before taking out our wallet’s. MIT professor Sherry Turkle calls such items that anchor our identity "evocative objects." In her book Evocative Objects: Things We Think With, she explores how everyday things act as companions to our emotional lives and catalysts for our thoughts. As we shift to digital, we risk losing these tangible anchors.

Photo by Clay Banks on Unsplash

Photo by Clay Banks on Unsplash

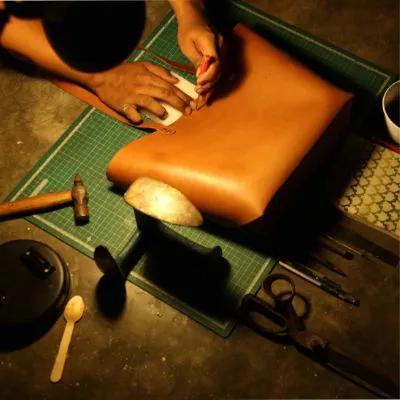

But this is not a eulogy. This is a call for renaissance. In the face of the digital ghost, the handmade leather wallet is having its moment. Choosing one today isn't about being old-fashioned. It is a deliberate act of rebellion—choosing texture over the sterile tap, story over raw data.

Carry Your Story in your Wallet

While digital tools offer efficiency, they cannot hold a story. A well-loved leather wallet doesn't just hold your valuables; it becomes one. It ages, it marks, it softens, and it absorbs the story of your life, your traditions, in its very creases.

In the end, the objects we choose to carry do more than serve a purpose; they help construct our reality. And a beautiful wallet holds a promise—a promise that we will choose to carry our stories with us, not just our data.

Photo by Noman Khan on Unsplash